“Dear Doctor” Letters to Reduce Opioid Prescriptions

Organization : B-Hub Editorial Team

Project Overview

Project Summary

To reduce opioid prescriptions, medical professionals were sent personal letters from the county medical examiner notifying them of a patient’s fatal overdose and outlining a list of prescription best practices.

Impact

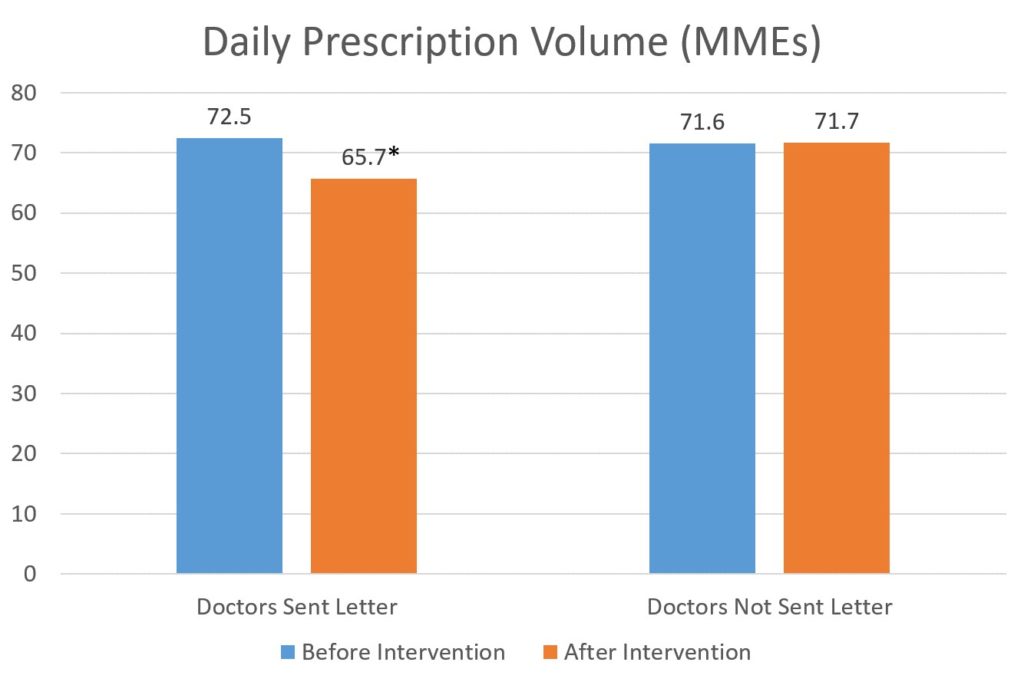

Letters to clinicians reduced the amount of opioids prescribed by 9.7%. Letter recipients also wrote fewer first-time and high-dose opioid prescriptions.

Source

Source

Challenge

Prescription and illicit opioid use accounted for more than 350,000 American deaths from 1999 to 2016. Intricately linked, prescription opioids can act as a gateway to illicit use, addiction, and overdose. Long-term, high dose opioid treatment has become more common as new pharmaceuticals have been introduced; since the 1990s, opioid addiction and related fatalities have led to a nation-wide epidemic. As of 2015, 1.9 million Americans suffered from opioid addiction. Safe and thoughtful prescription strategies can considerably reduce opioid addiction and misuse. Highlighting the risks of prescribing opioids has been shown to reduce the number and volume of opioid prescriptions written.

Design

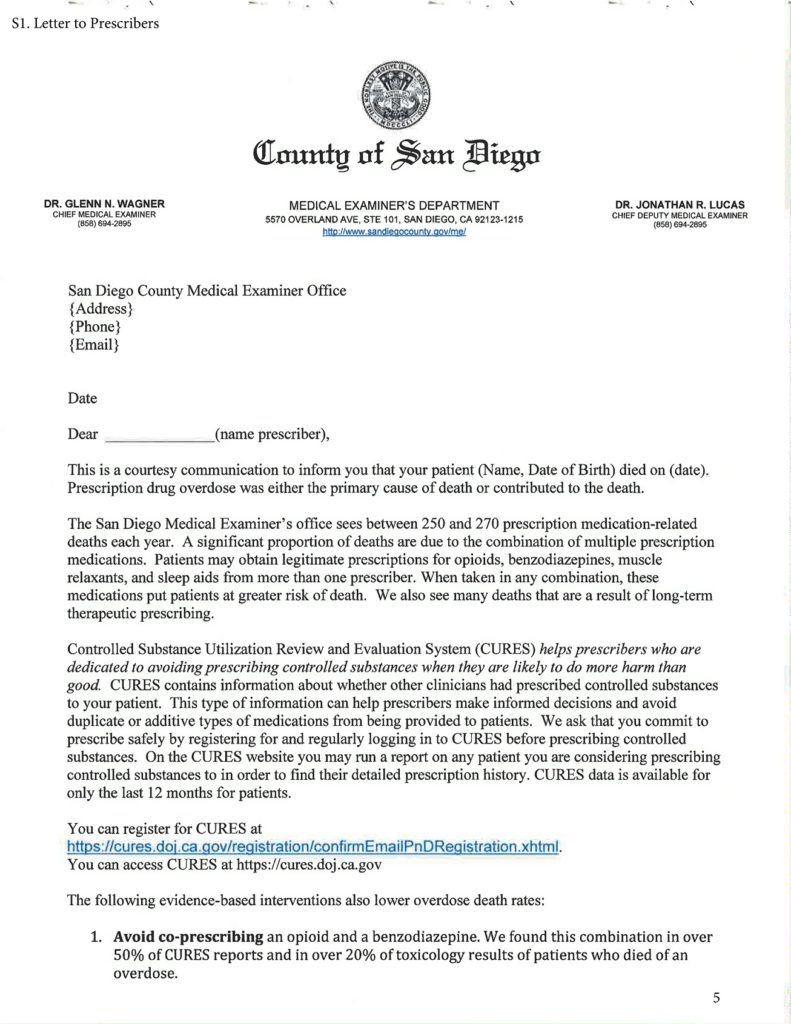

Clinicians were sent personal letters signed by the Chief Deputy Medical Examiner of San Diego County notifying them of their former patient’s death. The letter identified the patient by name, address, and age; recounted the number of annual prescription drug deaths seen by the medical examiner; promoted the state’s prescription drug monitoring program; and outlined five safe prescribing strategies recommended by the CDC. Only clinicians who had written a prescription filled by a patient within 12 months of their overdose death were contacted. The prescription behavior of 826 clinicians who had prescribed to 167 overdose decedents was recorded three months prior to the intervention and for a three-month period starting one month after the letters were sent.

Impact

A randomized evaluation found that a simple and informative letter sent to clinicians reduced opioid prescriptions filled up to four months later by 9.7% (in milligram morphine equivalents or MMEs), compared to prescriptions by clinicians not sent a letter. Clinicians who received a letter were also 7% less likely to start a new patient on opioids and between 3% and 4.5% less likely to prescribe high-dose prescriptions.

* Significantly different (p<0.05)

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researcher:

Would this work elsewhere?

- This study took place in San Diego; while the County’s diversity may be broadly representative of medical providers in the U.S., this intervention has not been tested elsewhere. However, this design is scalable, as all counties track prescription opioid deaths and each state maintains its own prescription drug monitoring program.

Advice for Implementers:

- This study only included clinicians whose opioid prescriptions had been filled within 12 months prior to an overdose death. This allows for a more easily retrieved memory and immediate connection than recalling a patient from years prior.

- Establish a method for gathering necessary data, and linking patients to clinicians. In this study the medical examiner investigated deaths for which a schedule II, III, or IV prescription drug was identified as a cause of death. Clinicians were matched to these deaths by using the Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation Systems database.

- Notifying of a single death and providing clinicians with data on the local number of annual overdoses brings to mind the patients who do not return for regular refills. This can counteract clinicians’ disproportionate exposure to the patients who return to refill their prescriptions.

- The letters were edited by an advisory group to ensure they were supportive in tone; a letter that takes a reprimanding tone may elicit different results.

- Having the medical examiner, a third party with perceived authority, send the letter encourages cautious prescribing without restricting freedom, such as by imposing mandates.

- This study followed clinicians’ prescribing behavior from one to four months after the letters had been sent. Since the outcome observed was prescriptions filled by patients, the first month after the letters were sent out was excluded to avoid prescriptions that may have been written prior to receiving the letter, but filled afterwards.

Project Credits

Researchers:

Jason N. Doctor Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California

Andy Nguyen Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California

Roneet Lev Emergency Department, Scripps Mercy Hospital San Diego

Jonathan Lucas Department of Medical Examiner-Coroner, Los Angeles County

Tara Knight Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California

Henu Zhao Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California

Michael Menchine Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Southern California