Beautiful Home: Reducing Alcohol Use to Prevent Intimate Partner Violence

Organization : ideas42

Project Overview

Project Summary

Married men in Bangalore received monetary incentives for their sobriety, and some additionally received behavioral couples therapy on topics such as alcohol use and communication.

Impact

Incentives paired with behavioral couples therapy significantly reduced alcohol use among male partners – their proportion of negative breathalyzer samples (96%) was 20 percentage points higher than a control group – and their female partners reported a nearly 50% reduction in violence experienced four months later.

Challenge

Globally, 35% of women have experienced gender-based violence and the vast majority is perpetrated by partners. Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is a fundamental injustice that affects the mental and physical well-being of survivors, their families, and broader communities. While many circumstances can contribute to violence, researchers working in IPV have long recognized that alcohol consumption is an important factor. Hazardous drinking impairs problem solving and cognitive abilities, while lowering inhibitions and increasing risk-taking. Anecdotal and empirical evidence demonstrates that men returning home after a night of drinking are more prone to aggression, increasing the risk of violence toward their partners. A recent report by the World Health Organization includes men’s alcohol use as a risk factor for IPV and suggests the need to generate additional evidence on alcohol misuse interventions for violence prevention.

Design

Beautiful Home is a 2-pronged intervention aimed at reducing male alcohol consumption and preventing IPV that was developed with input from community partners and piloted in Bangalore, India. The design was based on evidence that 1) incentive-based interventions have successfully reduced alcohol consumption by compensating men for sobriety and stimulating immediate behavior change, and 2) behavioral couples therapy (BCT) interventions have been shown to successfully reduce alcohol use and IPV by building skills and strategies to sustain behavior change over time. BCT helps both partners identify and practice specific behaviors that contribute to a positive relationship, such as expressing gratitude or controlling aggression. 60 married couples recruited through community-based outreach in Bangalore were randomly assigned into one of three arms: a control arm, an incentive-only arm, and an incentive plus counseling arm:

Control – Men were prompted every other day via cell phone voice messages to breathe into their breathalyzer and received a fee for participation.

Incentives – Men received a twice-daily prompt to blow into the breathalyzer. They received a participation fee each time they blew into the breathalyzer and could also earn additional monetary incentives for each negative breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) score. During the orientation session, couples learned how the incentives were dependent on the BrAC scores and participated in a goal-setting exercise to jointly decide on goals they would like to save their earnings for.

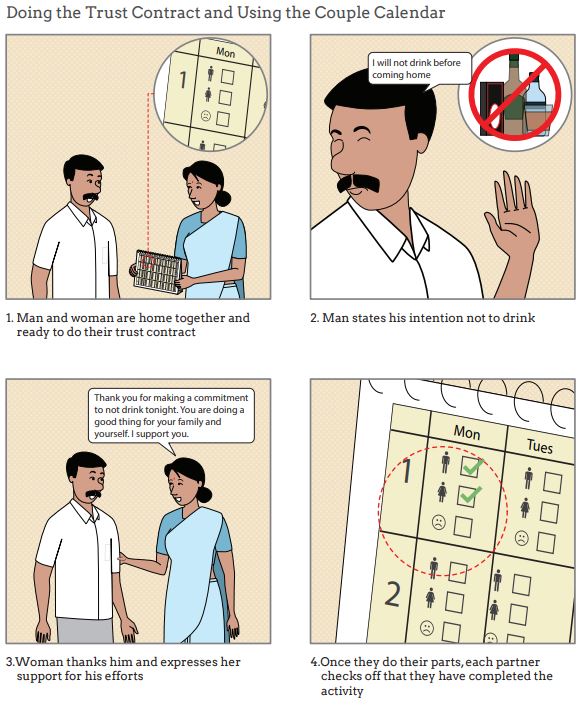

Incentives plus behavioral couples therapy (BCT) – Couples participated in the same activities as the Incentives group, as well as four weekly 1-hour BCT sessions on topics such as alcohol use and communication. Couples were asked to complete at-home assignments after each session, such as a daily trust contract in which the male partner was asked to state his intent to not drink and his female partner would in turn express support for his effort, with discussions logged on a daily calendar. Eight comic strips and graphics commissioned from a local artist helped to reinforce lessons and skills taught in the sessions.

BrAC levels were regularly collected from men over 4 weeks. All participants completed surveys prior to and after completion of the intervention, as well as during a 4-month follow-up visit.

Impact

A randomized evaluation found that pairing incentives for sobriety with BCT significantly reduced alcohol consumption in men; the proportion of negative BrAC samples tested during the study increased by 20 percentage points in the incentives plus BCT arm compared to the control arm (96% vs 76%, p<.05). Alcohol use was reduced in the incentives-only arm as well (93% of samples negative), but was not significantly different from the control group.

Additionally, violence reported by women in both intervention arms decreased significantly. At the end of the intervention, overall mean violence scores using a locally validated scale had decreased by 9.9 points (p<.001) in the incentives plus BCT arm. This effect persisted to the 4-month follow-up visit resulting in a mean violence score 13.3 points lower than baseline (p<.001). Moreover, the incentives-only arm also had a significantly lower score (-11.7 points) at 4 months compared with baseline (p<.001), while there was no significant difference in scores among the control couples. Decreases of this magnitude on this scale represent a 30% and nearly 50% reduction in violence among incentives-only couples and incentives plus BCT couples, respectively. The decreases in scores were primarily driven by men being less controlling of their female partners, which may have resulted from improved communication skills and emotional regulation.

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researchers:

- BCT sessions began 2 weeks after the incentives portion had started to allow the male partner’s alcohol use to stabilize and to mitigate any potential volatility. This is standard practice for BCT counseling.

- BCT sessions were conducted by lay counselors who had prior social work experience and who had been trained on BCT facilitation as part of the preparation for this study. The topics and content of the sessions were adapted with the support of BCT experts to reduce the likelihood of escalation to violence during or after the sessions; any discussion about the relationship, feelings, or anything not value-neutral was specifically removed. Counselors were supervised by a senior clinical psychologist trained in the provision of BCT, who observed a total of eight sessions per counselor to assess for quality and fidelity, using an observation checklist including measures such as the duration of the session, the level of participation during the session, the performance and enthusiasm of the counselor, and fidelity to the session plan.

- Alcohol use by male participants was based on BrAC as captured by the Soberlink® breathalyzer. The breathalyzers were programmed to request a test at a random time within a fixed 1-hr window. For the intervention arms, participants were tested twice per day out of concern that a single test point might be cue to drink rather than reinforce sobriety. The time windows for testing differed by week to compare monitoring protocols, the results of which were consistent. The he first test was always requested between 8:00 and 9:00 p.m. For Weeks 1 and 3, the second test was between10:00 and 11:00 p.m., and for Weeks 2 and 4, the second test was between 7:00 and 8:00 a.m. the next morning. The control arm was randomly tested every other day between 8:00 and 9:00 p.m. A negative BrAC test was defined as BrAC of under 0.01 g/dL.

- During the study, men came into the office to receive a portion of their participation and breathalyzer test rewards weekly. However, the majority of their earnings were placed in a savings account and transferred into participants’ bank accounts at the end of the study. This approach was designed to account for logistical concerns around the amount of cash that would need to be available and community partners’ concerns over how the money would be used.

- Violence experienced by female participants was measured using an adaptation of the Indian Family Violence and Control Scale (IFVCS), a culturally tailored scale for assessing a range of violent behaviors, which has been tested and validated previously in India. The IFVCS is a 63-item questionnaire, divided into four domains: control, psychological, physical, and sexual violence. For this study, the sexual violence domain was omitted in consultation with the community partner, given the sensitivity of the items, leaving 51 items.

Project Credits

Researchers:

Saugato Datta ideas42

Vivien Caetano ideas42

Rachel Banay ideas42

Rosii Floreak ideas42

Hannah Spring ideas42

Miriam Hartmann RTI International

Erica N. Browne RTI International

Prarthana Appiah St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India

Anurada Sreevasthsa St. John's Research Institute

Susan Thomas St. John's Research Institute

Sumithra Selvam St. John's Research Institute

Krishnamachari Srinivasan St. John's Research Institute