Did You Get Your Shots? Timely Reminders for Vaccinations

Organization : Inter-American Development Bank

Project Overview

Project Summary

Data suggests that families in rural Guatemala recognize the value of vaccination by getting their children vaccinated at early ages but fail to follow through with their plans as their children get older. In this experimental intervention, community health workers were given monthly lists of children due for vaccination at the clinic, enabling them to send timely reminders to families.

Impact

Reminders increased the likelihood that children completed their vaccination treatment by 2.2 percentage points in the treatment communities. For children in treatment communities who were due to receive a vaccine, and whose parents were expected to be reminded about the due date, the probability of vaccination completion increased by 4.6 percentage points.

Cost

The cost per additional child with complete vaccination due to this intervention is estimated to be around $7.50.

Challenge

In recent years, Guatemala has implemented supply-side interventions to boost vaccination rates: vaccines are provided free, and there are constant efforts to ensure that they are always available. In the mid-1990s, the government established the Coverage Extension Program (PEC), a program providing free basic health care services to children under the age of five and women of reproductive age, with a focus on preventive care. The Ministry of Health then hired local NGOs to operate a network of rural basic clinics in which health workers are expected to track individual families and inform them when they should attend the monthly mobile medical team’s visit. However, there are no clear guidelines and communication depends on health workers’ initiative.

As a result of all combined efforts, vaccination rates have increased dramatically. However, while coverage rates for vaccines due in the first months of life are high, they decrease markedly for vaccines due after children turn one year old. These patterns suggest that families recognize the value of vaccination and may be willing to incur the (time) costs involved in having their children vaccinated, but often fail to follow through with their plans to complete the vaccination cycle.

Design

The intervention consisted of randomly assigning 130 basic clinics operated by NGOs under PEC to a treatment or a control group. In treatment communities, health workers received lists of children who were due to receive a vaccination at the clinic in the following month, enabling them to send timely reminders to families.

The lists were distributed to community health workers at monthly meetings at the NGO offices, along with information on the medical team’s upcoming visit to their clinic. While health workers in all PEC communities are expected to provide some kind of reminder, health workers in treatment communities received concise, up-to-date information on which families to remind, whereas health workers in control communities had to rely on their own records, which they may or may not have created and maintained. The specific type of reminder depended on the initiative of the workers. After six months of implementation, the rate of children that had received all vaccines recommended for his or her age (complete vaccination) was compared among groups.

Impact

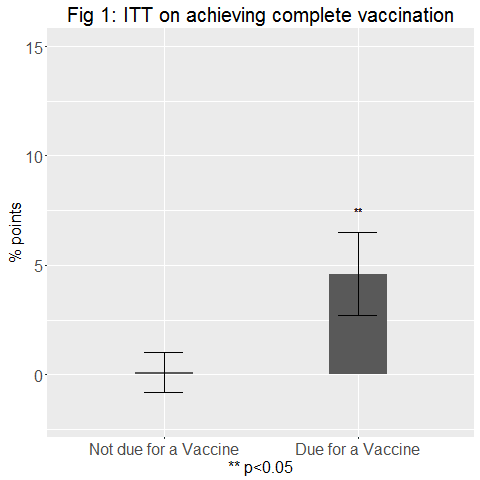

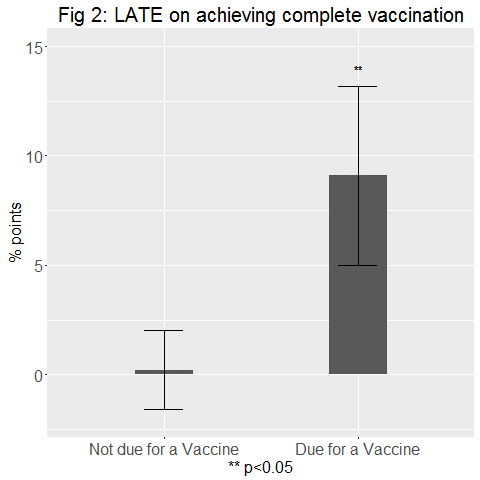

The intervention increased the probability of vaccination completion by 2.2 percentage points among all children in treatment communities (ITT). For children in treatment communities who were due to receive a vaccine, and whose parents were thus expected to be reminded about that due date, the probability of vaccination completion increased by 4.6 percentage points (Figure 1). The LATE estimate shows a stronger effect, increasing the probability of complete vaccination by 4.5 percentage points for all children in treatment communities and 9.1 percentage points for children due for a vaccine (Figure 2). Estimated effects for children of parents not expected to be reminded are essentially zero, suggesting that the intervention did not generate spillovers for these children within treatment communities.

Comparison of effect on children due for a vaccine to children not due for a vaccine, within treatment communities. ITT = intent to treat (participation is defined as whether a community health worker was assigned to the treatment group).

Comparison of effect on children due for a vaccine to children not due for a vaccine, within treatment communities. LATE = local average treatment effect (participation is defined as whether community health workers indicated in the endline survey that they actually received the new patient lists)

The overall effects of providing reminders are remarkable in light of its low cost. The estimated total cost of scaling up this intervention in Guatemala is only $0.17 per child for the six-month intervention. Hence, the cost per additional child with complete vaccination due to this intervention is expected to be around $7.50. Reminders were found to be a cheaper tool than others (such as conditional transfers) to increase immunization. The low cost-to-benefit ratio makes this a scalable option for other goals, such as malaria.

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researcher:

- The PEC’s administrative records were used to generate lists of patients due for preventive health services. These lists include detailed information on the type of service individuals need (on a monthly basis), enabling community health workers to give specific and timely reminders to families. The lists group patients by neighborhood, then households, while services are grouped by type. A typical list might include 20 homes and 30 individual patients due for 90 services, on two sheets of paper.

- Communities served by the PEC can receive medical services locally only on the date of the mobile medical team’s monthly visit. Therefore, community health workers’ reminders play an important role in receiving health care. The reminders could increase demand for preventive health services by helping patients remember to take their children to health clinics to receive these services. Alternatively, the reminders could highlight the importance of receiving vaccines according to the recommended schedule and, hence, reminders could be seen as providing information about their value in a more indirect way.

- To implement the intervention, a software developer wrote a program that produced the patient lists. Additional staff was hired to produce the lists every month in each of four study areas for the clinics that were randomly assigned to the treatment group. These four staff members were aware of the study’s experimental design and understood that they should not distribute the lists to clinics assigned to the control group. At the community health workers’ monthly meetings at the NGO offices, facilitators distributed the lists with information on individuals in their communities that needed health services that month and the following month to the treatment group. Community health workers in the control group were aware of the study and may have observed the lists being distributed to health workers in the treatment group. If this fact made health workers in the control group increase their efforts to track patients in their coverage areas, this would lead to underestimating the treatment effects of this study.

Project Credits

Researchers:

Matias Busso Research Department, Inter-American Development Bank

Julian Cristia Research Department, Inter-American Development Bank

Sarah Humpage Mathematica Policy Research, Princeton, NJ