Refer-a-Friend to Family Planning

Organizations : Marie Stopes Uganda, MSI Reproductive Choices, ideas42

Project Overview

Project Summary

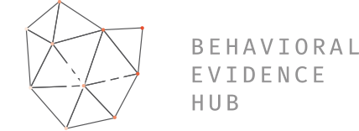

Adolescent girls who have received family planning counseling or services are given a Refer-a-Friend (RAF) card from a provider or community mobilizer to share with their friend. Girls redeem RAF cards at the clinic for a pair of friendship wristbands – one for her and one for the friend who referred her, and optional free counseling. In-clinic materials help to create an adolescent friendly environment.

Impact

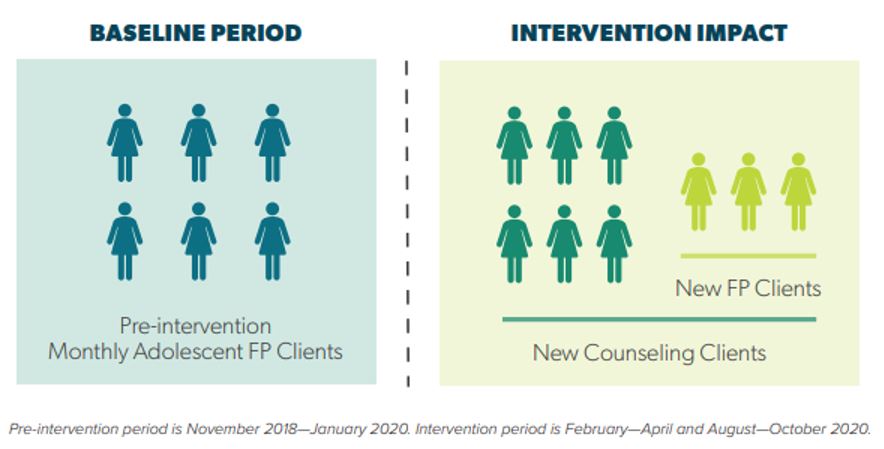

The intervention increased the average monthly number of adolescent girls receiving family planning services per clinic by 45% compared to baseline and relative to control clinics. Similarly, the adolescent proportion of all family planning clients in intervention clinics increased by 5.3 percentage points on average.

Challenge

Unplanned pregnancy can dramatically impact an adolescent’s health and economic future. Pregnancy and childbirth complications are the leading cause of death for girls aged 15-19 and pregnancy is the most common reason for school dropout. In 2016, 25% of adolescent girls aged 15-19 in Uganda had begun childbearing, yet nearly half of those births were reported as mistimed or unwanted [1]. Six in ten girls who are sexually active and do not want a child for at least two years have an unmet need for modern contraception [2]. To address the challenge of unmet need for family planning (FP), particular attention is needed to ensure that adolescents have meaningful access to youth-friendly counseling and services to support their informed choice. Interventions aimed at adolescents still forming their identifies and developing their understanding of norms around sexuality and gender may be especially critical in contexts where social stigma can be a barrier to contraception uptake.

Marie Stopes Uganda (MSUG) provides approximately 60% of all contraception in Uganda through a range of channels targeting different under-served populations. The “BlueStar” network of 151 private sector Social Franchise clinics delivers services in urban and peri-urban communities with support, training, and equipment from MSUG. Community-based mobilizers raise awareness and generate referrals for services offered at clinics. A behavioral diagnosis through clinic-based observations and qualitative interviews with adolescents, providers, mobilizers, and MSUG staff revealed behavioral barriers limiting adolescent FP uptake and suggested opportunities for design.

Design

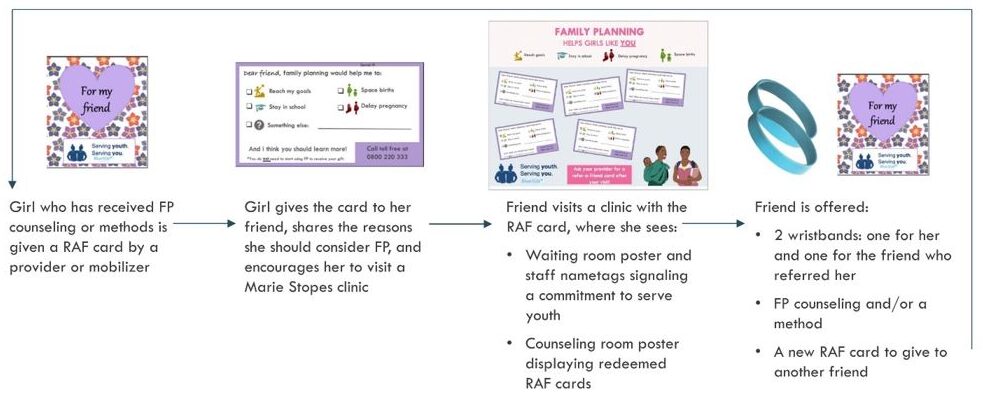

Based on diagnosis insights, ideas42 in collaboration with MSUG and MSI Reproductive Choices designed an intervention to increase adolescent uptake of FP services, which was refined and iterated on through collaborative user-testing. The resulting multi-channel intervention targets adolescents, mobilizers, and service providers.

The core intervention is primarily a peer-referral system formalizing word-of-mouth channels, intended to reduce stigma and normalize adolescent information sharing and service uptake. The program enables girls aged 15-19 who use contraceptives or have received counseling to offer a “Refer-a-Friend” (RAF) card they received from a provider or mobilizer to a friend not currently using contraceptives. Girls redeem their RAF card at BlueStar clinics for a pair of friendship wristbands – one for her and one for her referring friend – and free contraceptive counselling. Girls are not required to accept counseling or take up an FP method to receive wristbands.

The program offers girls an immediate incentive to talk to friends about FP, share advice, and articulate reasons why girls like them may choose to use contraceptives. Girls who receive RAF cards get an endorsement from a trusted peer, empowering those who might otherwise feel uncomfortable to seek services, while girls who give cards have opportunities to give advice that builds their confidence and solidifies their motivation to access FP services when needed. When a girl visits a clinic to redeem a card and receives contraceptive counseling or services, she receives a new card to give to another friend, becoming an advice-giver herself. In-facility materials, including posters welcoming adolescent girls and displaying redeemed RAF cards and badges worn by facility staff, help to create an adolescent-friendly environment. Half of intervention clinics additionally were randomly assigned to receive a 3-day staff training on youth-friendly service provision. The program was implemented across 6 months of 2020, with a 3-month pause halfway through due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Impact

A randomized evaluation found significant (p<.01) positive impacts of the intervention on both primary outcomes compared to a baseline period and relative to a control group of clinics that did not receive the intervention – a 45% increase in the average number of monthly adolescent clients (about 5.4 more per clinic) and a 5.3 percentage point increase in the average monthly adolescent proportion of FP clients. This suggests that nearly 2,000 adolescents became new FP users as a result of the intervention during the six months of implementation. Since not all adolescents who received FP counseling took up a method, participation in counseling is an arguably greater impact of the intervention although not captured in administrative data. RAF card redemption figures, although incomplete, suggest that for every adolescent girl who took up FP, at least another two girls may have received FP counseling to support their informed choice at a later time.

Visual representation of impact in a small BlueStar clinic

We found marginally stronger effects of the intervention when paired with the youth-friendly services training – those clinics saw a 62% relative increase in monthly adolescent clients (7.4 more per clinic) compared to a 26% increase (3.2 adolescents per clinic) when the intervention was implemented without the training.

Although the randomized controlled trial found significant results across the full intervention period, effect sizes were strongest during the initial months of implementation, suggesting that factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic may have weakened the impact of the intervention during and immediately after the country-wide lockdown.

Implementation Guidelines

Inspired to implement this design in your own work? Here are some things to think about before you get started:

- Are the behavioral drivers to the problem you are trying to solve similar to the ones described in the challenge section of this project?

- Is it feasible to adapt the design to address your problem?

- Could there be structural barriers at play that might keep the design from having the desired effect?

- Finally, we encourage you to make sure you monitor, test and take steps to iterate on designs often when either adapting them to a new context or scaling up to make sure they’re effective.

Additionally, consider the following insights from the design’s researchers:

- Care should be taken not to interfere with girls’ choices of whether and when to take up a contraceptive method. RAF cards can be redeemed for wristbands and free counseling regardless of whether the girl redeeming the card chooses to access additional services. MSUG clinic providers were instructed to provide wristbands upfront when a RAF card was presented so girls did not feel pressured to accept or stay for services. The greater number of RAF cards redeemed and wristbands distributed relative to the increase in FP users suggests that most girls felt comfortable to turn down services. Interviews with adolescents as part of a process evaluation also did not reveal any instances where girls felt pressure or coercion to accept services.

- RAF cards may be useful in a broader range of instances than the program originally envisioned. Providers and community mobilizers were instructed to only distribute RAF cards to adolescent girls aged 15-19 who were satisfied users of FP or FP counseling. Adolescents could only give RAF cards to friends who were also aged 15-19. However, some MSUG staff found the distribution restrictions too limiting and suggested that the program allow older women and boys to also refer adolescent girls with RAF cards. Mobilizers also found that the RAF cards were an effective tool for referring non-FP users straight to the clinics. Implementers should consider whichever of these adaptations would work best for their setting.

- Discretion and anonymity are critical to the program’s success and participants’ safety. This program’s materials were intentionally designed to be recognizable and attractive to youth, while also ensuring discretion, given that concerns over visibility and privacy were identified as a significant barrier to FP uptake during diagnosis. Girls both reacted very positively to the wristbands and design materials and expressed relief to know that their name or personal information would not be included on cards or posters. They were willing to participate in the RAF program because they felt assured that they would not receive unwanted attention or reveal themselves as FP users to anyone they did not want to. If the program is adapted to other settings, the safety and comfort of the girls participating warrants special attention and may require adjustment of the materials or additional training for the providers and mobilizers distributing them.

- The program may be effective in settings where FP services are available at no cost to clients as well as where they are not. A subset of BlueStar clinics participate in a program through which vouchers subsidized to reduce or eliminate costs to girls and young women are distributed or sold in the community through mobilizers. The evaluation found a marginally significant positive interaction between the intervention and the availability of free FP services for adolescents, which suggests demand generation efforts are best paired with measures to increase affordability. However, the intervention still had a significant, and relatively stronger, impact in clinics not participating in the voucher program, which had a smaller adolescent client volume at baseline. These results underscore the intervention’s potential even where resource constraints make it impossible to offer free services.

- Find more considerations for implementation and adaptation in the program’s design guide.

Project Credits

Page submitted by:

More projects from this organization

More projects from this organization

More projects from this organization

More projects from this organization

More projects from this organization

More projects from this organization

Researchers:

Sara Flanagan ideas42

Arielle Gorstein ideas42

Emily Zimmerman ideas42

Martha Nicholson MSI Reproductive Choices

Stephanie Bradish MSI Reproductive Choices

Diana Amanyire MSI Reproductive Choices

Andrew Gidudu Marie Stopes Uganda

Francis Aucur Marie Stopes Uganda

Julius Twesigye Marie Stopes Uganda

Faith Kyateka Marie Stopes Uganda

Samuel Balamaga Marie Stopes Uganda

Alison Buttenheim University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing